by Linda Wulf | Aug 15, 2025 | Main Blog |

Content Warning:

This essay discusses cancer, medical trauma and contains strong language, which may be triggering.

Spoiler Alert of Brain Cancer

I’m absolutely fine—better than ever, actually. Older, yes, and certain I’ll die one day—but not from brain cancer, not from the treatments, and definitely not anytime soon. No, it wasn’t a misdiagnosis, and yes, contrary to popular opinion, the body can heal itself.

It’s been a wild ride since December 3, 2023, when I scribbled in my journal: “Sitting at Mayo, expecting a brain tumor diagnosis.” In those early days, my thoughts were simple. When your brain’s a mess, articulating what’s happening is tough. But for caretakers of someone who seems impaired, trust me: we hear everything. I heard my husband mumbling about my outbursts, the doctor saying, “That doesn’t make sense,” and me, unable to clarify.

Two days later, on December 5, 2023, I journaled:

The tumor was inoperable but treatable. Chemotherapy could stop its progression. We awaited pathology reports.

Countless tests—MRIs, PET scans, biopsies, blood draws—led to the diagnosis: Primary CNS DLBCL—Central Nervous System Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Grok, an AI assistant, summarizes: It’s a rare (1,500–1,700 cases yearly), aggressive lymphoma, treated with methotrexate. Five-year survival is 30–50%.

The prognosis felt bleak, but I was relieved—so relieved—it wasn’t Alzheimer’s, unlike my mom and five aunts. It explained my struggles: botched recipes, car crashes, hallucinations. I’d watched my parents die—Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s—and vowed I’d rather drop dead than linger in a nursing home, medicated into oblivion.

My husband, Tim, faced the awful choice—guided by experts in a life-or-death rush. On November 27, 2023, after a family intervention—Tim and my stepson, Andrew, all but carrying me to Mayo—I arrived disoriented, albeit clearer from antibiotics started days earlier for a chronic dental infection, battled with quarterly visits for three decades. Over 13 days, Mayo was my universe: MRIs, CT scans, brain biopsy, spinal taps, EEGs, blood draws. Antibiotics tackled the infection; steroids calmed brain inflammation. It made sense—clear the infection, shrink the swelling and stabilize the chaos.

By December 8, methotrexate began, a Primary CNS DLBCL standard, but the protocols stopped making sense to me. On December 18, I dug into PubMed, emailing Dr. Mrugala a study on titanium implant neurotoxicity and CNS Lymphoma1, suspecting my 2011 dental implant. No reply. On December 21, a facial CT scan—likely from my complaints—went nowhere. When I demanded a titanium blood test, a resident shrugged, “What would we do with that? We don’t do teeth.” In my foggy mind, I thought, “Can’t you see the connection between my lymph system and my inflamed gums, inches away?

During downtime, I reflected on vomiting incidents—first beer, first cigarette, and years ago, nearly puking entering a church I’d run from, a gut-punch rejection of something that felt wrong. My body knew poison, chemical or not. On my first day of at-home chemotherapy, I took temozolomide (Temodar) without anti-nausea meds—thinking I could tough it out. Within minutes, I was lying on the bathroom floor or hugging the toilet, vomiting.

The tile’s coolness eased the retching; my thoughts spiraled: I can’t do this. Why didn’t I call friends with cancer? I suck for being a bad friend. Thank God for temozolomide. I’d been giving thanks for everything, good or bad. Days later, an epiphany: RAT BASTARDS! Anti-nausea pills masked temozolomide’s poison. I researched and learned temozolomide—unproven for lymphoma, meant for glioblastoma, with claims it could “get past the blood-brain barrier”—could wreck my lymphocytes. That dissolving sensation in my head from that chemotherapy week? I’d feel it again 72 hours into my first fast to induce neural autophagy.

I stopped temozolomide after that week, but methotrexate lingered. On January 17, 2024, I arrived for my fourth in-hospital methotrexate, defiant, wanting my teeth fixed. My husband, terrified of losing me, insisted I listen to the experts. Reluctantly, I went but refused anti-nausea meds to let my body react. Dr. Walker, a young resident, implied I’d lost my mind, suggesting my cognitive functions were impaired. I challenged him to check my recent cognitive tests. I didn’t want to be tossed out of Mayo or “divorced” from Dr. Mrugala, one of the world’s best. What if I was wrong about my teeth and the tumor returned? I’d lose precious time.

So, I let my guard down and shared my vomiting insights—cigarettes, alcohol, that church moment. An hour later, the neuro-oncology team gathered, eyeing me like a wild card: Dr. Mrugala, head of neuro-oncology, smiled curiously; the floor doctor, a sharp Jewish woman in her 30s, insisted I not puke on her floor; Dr. Walker stood with them, having listened. I held up my “FEAR NOT” vision, my mantra since November:

“WE are fearfully and wonderfully made2.”

“And F*!# cancer!

“It’s my teeth—you don’t see it? One last methotrexate, then I fix my teeth.” On January 21, 2024, I stopped all chemo. I ordered a $119 titanium blood test through Request A Test3, which confirmed traces of titanium, though nothing else. On February 2, 2024, my dentist confirmed an ongoing infection in my problematic tooth, fueling my resolve. My next essay, “Power in the Blood,” reveals how I stumbled into healing through breath.

Notes

by Linda Wulf | Jul 21, 2025 | Main Blog |

Realizing the Chemical Load

About this time last year—July 2024—I started doing one of those strange and sobering things people do when they begin consciously preparing for the end: clearing out clutter, sorting through forgotten corners of the house, and asking what matters. That beautiful July day, I found myself sorting through my stuff, trying to make things easier for whoever might someday have to deal with it—asking: What to keep? What to toss? Why do I even have this?

While scanning my shelves for books I could let go of, I paused at a volume that had followed me through several moves. I had boxed it up and shipped it west over a decade earlier from my mother’s house, when I was helping her relocate for what would be her final days. She passed in 2014, but the book had remained unread on my shelves ever since—until now, when I was beginning to contemplate my own demise.

The book was titled Du Pont: The Autobiography of an American Enterprise, published in 1952 to commemorate the company’s 150th anniversary. Inside was a mimeographed letter addressed to my mom, who had worked in Du Pont’s advertising department that year.

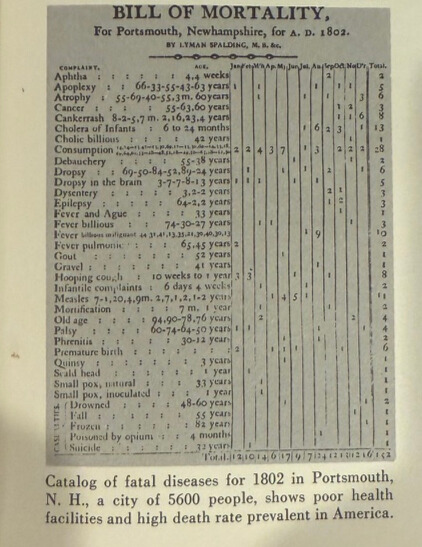

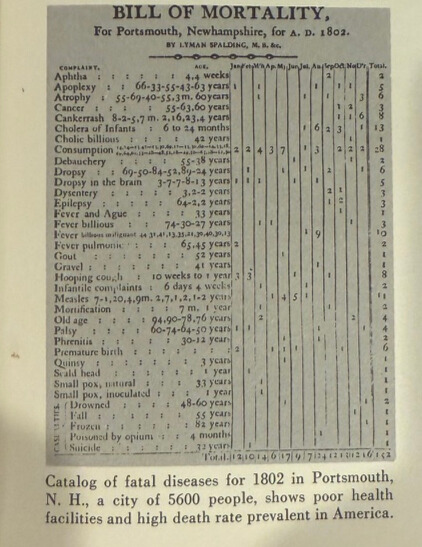

What ultimately caught my attention wasn’t the corporate history but a curious image printed on page 5: the “Bill of Mortality for Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for A.D. 1802.” A stark ledger of the 152 people who died that year in a small New England city. The typed and handwritten entries listed causes of death from “Aphtha” to “Suicide,” and I found myself drawn in—not just by the details, but by the contrast to now. What were we dying from then, compared to today?

Figure 1: Bill of Mortality, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1802, printed in DuPont: The Autobiography of an American Enterprise (1952), showing 152 deaths, mostly from infectious diseases like cholera, measles, and whooping cough. Only three cancer cases were noted, with minimal neurological mentions.

As I studied the faded image, the differences were profound. In 1802, only three deaths were attributed to cancer and none to heart disease—conditions that today account for nearly half of all U.S. deaths. Neurological illnesses were also uncommon, with just twelve cases listed under older terms like “apoplexy,” “epilepsy,” and “palsy.” Instead, the ledger was filled with infectious threats: measles, cholera, whooping cough, and dysentery.

Of the 152 total deaths recorded in Portsmouth that year, 50 were children under the age of 15, including six premature births. In a world with no antibiotics, no vaccines, and poor sanitation, the greatest threat to life was microbial—not metabolic. Chronic illness was rare, and survival into old age, while possible, was far from guaranteed.

By the 1930s, the landscape of death had shifted dramatically. Infectious diseases that once dominated life had been largely tamed by antibiotics, vaccines, clean water systems, and public health reforms. In 1906, the Pure Food and Drugs Act was passed, and enforcement was assigned to the Bureau of Chemistry—the early predecessor to today’s FDA. It wasn’t until 1930 that the modern Food and Drug Administration was officially named. These were triumphs. Life expectancy rose. The killers of 1802 were, it seemed, under control.

But as I lingered over that 1802 ledger, a different question came into focus: If we’d conquered those ancient plagues, why are we now dying from cancer, heart disease, and neurological disorders at rates unimaginable two centuries ago?

That’s When It Hit Me

We had traded one threat for another. Microbes for molecules. Today, the average American body is exposed to thousands of synthetic chemicals—every single day. And not in trace amounts. These are in our food, our packaging, our personal care products, our medicine cabinets—even the supplements we take to “stay healthy.” Unlike the short, violent threat of infection, this chemical load accumulates—quietly, invisibly—until something breaks.

As I began researching what became my article, The Toxic Web, I discovered the scale of the problem: 7,157 unique chemicals are actively used across FDA databases for food, drugs, packaging, and personal care products. Many have never undergone a meaningful safety review. Others were grandfathered in decades ago under loopholes like GRAS—”Generally Recognized as Safe”—which allow companies to self-certify ingredients without oversight.

And so my “aha” moment wasn’t just academic—it was personal. I realized: this is what we’re up against now.

So I made a change. A real one. I stopped waiting for someone to protect me. I eliminated every unnecessary chemical I could find—starting with my plate and my shower. No additives. No preservatives. No medications, over the counter or otherwise unless there was a clear, tested need. No more synthetic lotions, no more “natural” products with mystery ingredients. I cleaned up what went in and what went on.

This wasn’t a rejection of science. It was a return to balance. A conscious choice to stop feeding the silent storm brewing inside me.

Once I understood the scale of the chemical load we’re all living under, I began to do something both radical and simple: I started paying attention.

Not in a paranoid way. In a quiet, curious way. I began watching my body—closely—for how it responded to chemicals. I had downloaded the Yuka app months before, but now I was more aggressive, scanning every label I could find. What was in my lotion? My shampoo? My toothpaste? My almond butter? Every product had a backstory—often a toxic one. Most people around me assumed that if it was on a shelf, it must be safe. But I had stopped believing that. And what I started noticing confirmed my doubts.

Let Me Share with You One Moment in Particular

It was my granddaughter Bexly’s birthday, August 3, 2024. I went to her party trying to strike the balance I’d been practicing—avoiding additives without being a pain. I don’t want to be the crazy “Lola” who won’t eat anything. So that evening, I skipped the bottled salad dressing (most contain endocrine disruptors), had a little bit of salad greens knowing it might carry some pesticide residue, and then joined in the celebration: Papa Murphy’s pizza and a slice of commercially prepared birthday cake—frosted in its cotton-candy-colored glory.

I felt fine that night. It was so good—I hadn’t indulged in a sweet cake treat in months. But the next morning at 7 a.m., I stood up and was completely surprised by what happened. I jumped up and immediately realized my balance was completely off. The room was shaky. I wasn’t dizzy in the usual sense—I was disoriented. My equilibrium had collapsed. It took until nearly 1 p.m. before I started feeling normal again, like I could walk without tripping or falling.

In hindsight, I realized I had experienced a delayed neurotoxic response. The vivid dyes in that cake frosting—like Red 40 and Blue 1—are flagged by Yuka and others as neurotoxic and endocrine-disrupting. My nervous system had taken the hit. That incident wasn’t a fluke—it was my body’s response to the tiny bit of neurotoxins in that cake.

It occurred to me at that moment that maybe doctors shouldn’t just ask us “old folks” if we’re feeling off balance—they should be asking what kind of birthday cake we ate last night.

From that point on, I became meticulous and diligent about noticing. I cut out unnecessary chemicals wherever I could—ditching synthetic lotions, shampoos, and soaps. I had stopped taking supplements years earlier, after watching a close friend rapidly decline from glioblastoma. I couldn’t help but wonder whether the concentrated compounds she’d taken in an effort to “stay healthy” had, ironically, hastened her decline. It was only a hunch—but strong enough to change my behavior at the time.

I buy organic whenever possible. I practiced delayed eating—12 to 14 hours regularly. And I paid close attention to my own reactions—especially to subtle shifts: dry eyes, brain fog, mood changes, and fatigue. These became signals. Data points. Feedback.

This wasn’t about fear. It was about awareness—the act of noticing of listening to a body that had been shouting all along but had gone unheard.

And still, I live. I go out. I laugh with friends. I eat in restaurants—carefully. I don’t let vigilance turn into obsession. But now, I live by one rule: if I can avoid it, I will.

Because once you start noticing, you can’t unsee it. And once your body shows you the cost, you stop pretending the price is acceptable.

So that’s where I’ll leave this—for now. Just notice. Start there. Your body might be saying more than you think. Mine was.

by Linda Wulf | Jun 28, 2025 | Main Blog |

Data-backed remission after stopping chemotherapy. Breath, fasting, whole-food nutrition, and chemical-free living proved more than supportive—they may have been the key.

When I was diagnosed with primary CNS lymphoma in November 2023, I faced what medicine typically labels a grim prognosis. The lesion—deep in the corpus callosum—was declared inoperable. I underwent four chemotherapy sessions between December and January, but after reviewing the risks, the lack of testing for my cancer type, and the impact on my immune system, I made a different decision.

I stopped chemotherapy in January 2024—Cancer Recovery.

The decision to stop chemotherapy was a pivotal moment in my journey towards Cancer Recovery. I realized that taking control of my health was essential in my fight against this disease.

Since that time, I’ve followed a non-traditional but carefully reasoned path: breathwork, fasting, whole-food nutrition, and chemical-free living. It wasn’t about rejecting science—it was about asking the kind of questions science hasn’t yet fully answered.

Seventeen months later, the data is in: I remain stable, symptom-free, and stronger than ever.

Embracing a holistic approach, I discovered that each aspect of my lifestyle contributed to my Cancer Recovery. Breathwork, nutrition, and more became part of my healing process.

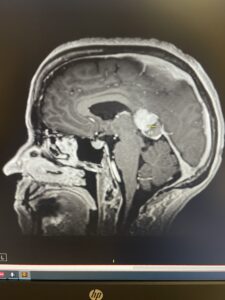

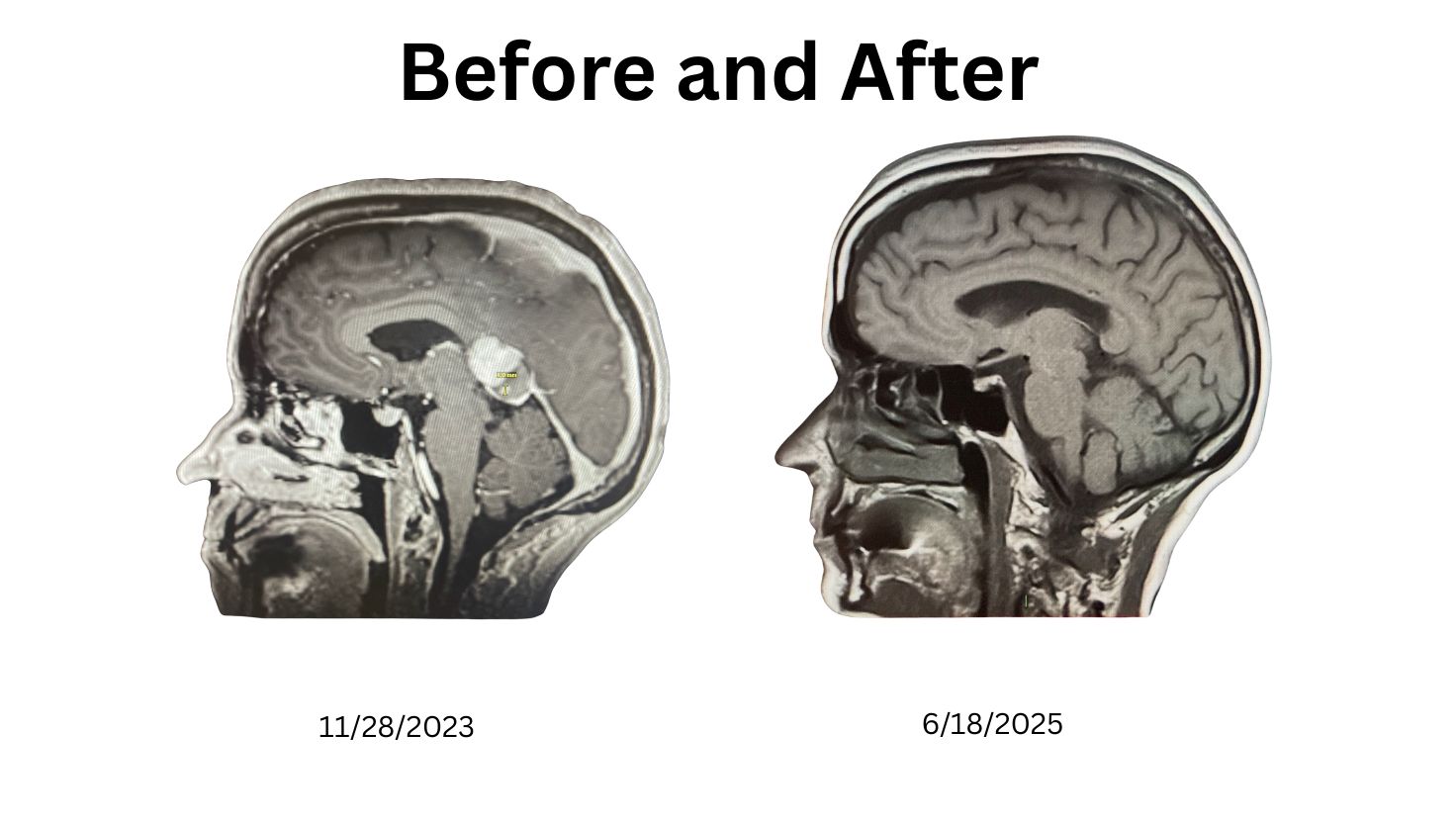

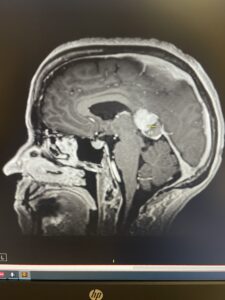

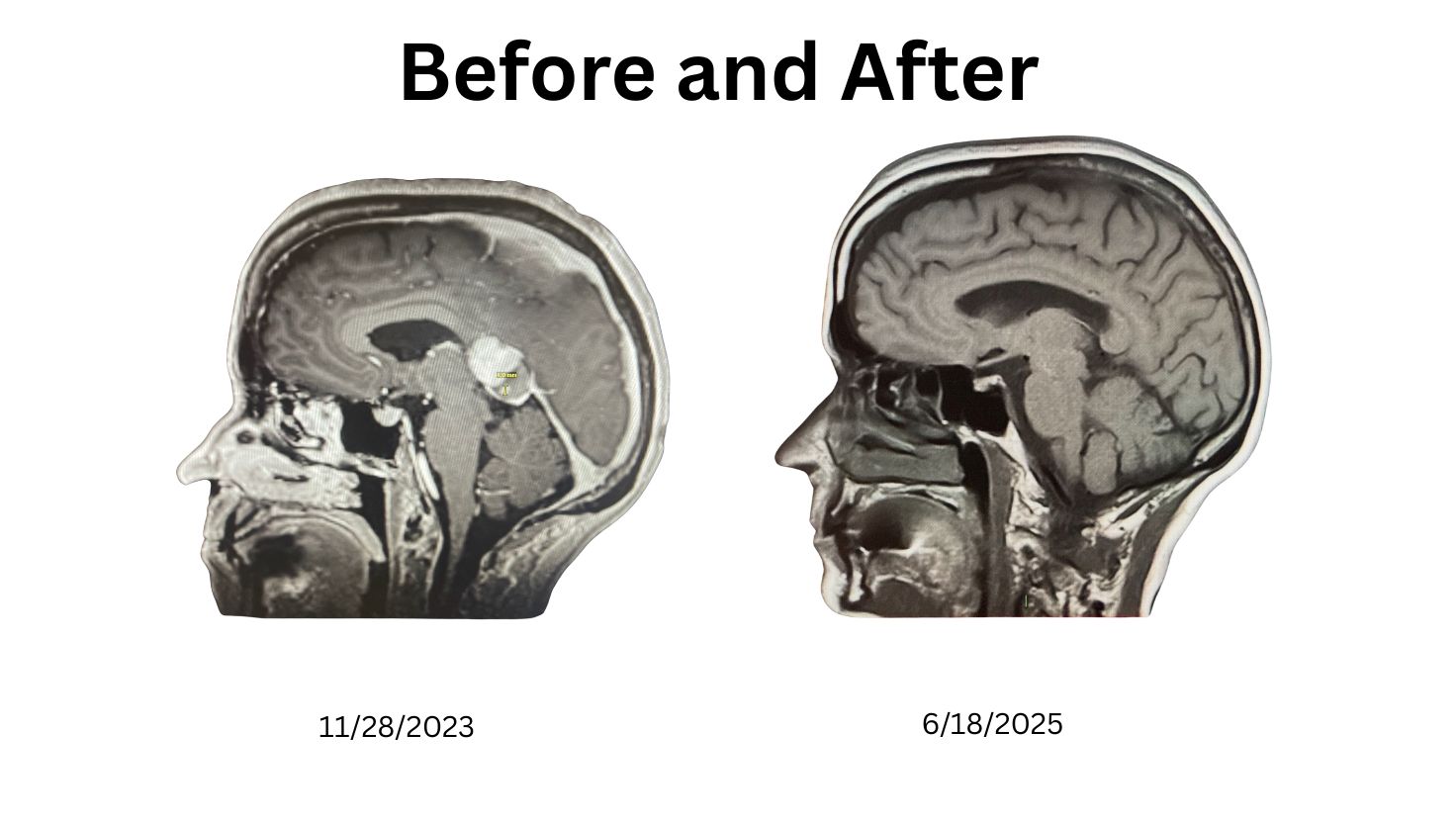

The Scans Tell the Story

Here is what my medical records show:

- November 28, 2023 (Mayo Clinic): A large tumor in the corpus callosum, likely CNS lymphoma, measuring nearly 5 cm.

- January 4, 2024: Scan taken during chemotherapy cycle shows “significantly decreased zone of T2 signal abnormality.”

- February 17, 2024: Continued improvement with “moderately decreased enhancement.”

- April 13, 2024: Mild residual lesion; no new abnormalities.

- July 17, 2024: No residual contrast enhancement. Described as “likely secondary to treated lymphoma.”

- October 30, 2024 ( non-contrast): Mild increase in brain signal noted, though no IV contrast was used to confirm active enhancement. I believe this was likely related to a dental infection that had not yet fully resolved.**

- June 19, 2025 (most recent): Stable post-biopsy changes. No masses. No new white matter signal abnormalities. No active disease.

- Since January 2024, I’ve had zero chemotherapy—and no confirmed tumor progression. This was clinically reaffirmed by my June 2025 MRI: no progression, no enhancement, no active disease.

** The October scan—while initially concerning—aligned with an ongoing dental issue. I had undergone a new implant procedure on June 12, 2024; the implant was noted to be loose by late June. On August 7, 2024, the implant was removed and infection was again confirmed. In hindsight, I believe the October scan reflected my body’s immune response to this lingering infection, not cancer progression.

What Changed: A Different Protocol

Instead of continuing chemotherapy beyond four sessions, I took a different path based on four key interventions:

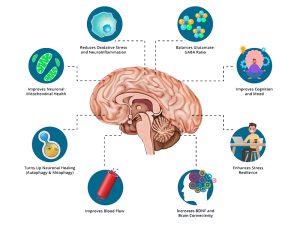

Breathwork

What began as a spiritual practice became, unexpectedly, a therapeutic tool grounded in measurable outcomes. I began practicing deep breathing on my own—largely freestyle but similar in rhythm to box breathing—well before I ever read James Nestor’s book. Months later, I discovered Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art and realized that some of his recommended techniques closely mirrored what I was already doing. His book outlines several scientifically supported methods.

I particularly recommend readers explore the breath-holding techniques and gentle head movements that, in my experience, seem to facilitate lymph fluid movement in the neck and head. These complemented practices like Wim Hof’s method, Buteyko breathing, and the protocols discussed across several episodes of Andrew Huberman’s podcast. Each episode covers different techniques with scientific depth—focusing on oxygen efficiency, tolerance, vagus nerve stimulation, and nervous system regulation. What started as a spiritual ritual morphed into biochemical experiments for me.

Breathwork may have done more than support my immune system—it helped eliminate something deeper. I’ve long believed my cancer originated from a chronic dental infection. Initially when I arrived at Mayo, I was given heavy antibiotics. Before I finalized the decision to leave chemotherapy, I visited my periodontist. It was during that visit that I began to realize that the breathwork had started to address the chronic aspect of the infection—its deep, embedded toxicity—was finally beginning to resolve itself. I now believe breathwork played a pivotal role in helping my body push out what had been stuck for decades.

The integration of various practices played a significant role in my Cancer Recovery. I learned how addressing every facet of health could lead to remarkable outcomes.

Fasting & Autophagy

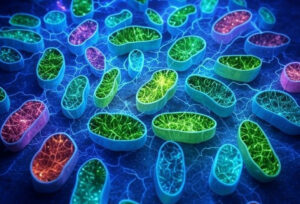

Early in the journey, inspired by physicians like Dr. Pradeep Jamnadas, I used intermittent and extended fasting to stimulate autophagy and mitophagy—mechanisms that promote the cleanup of damaged or malfunctioning cells, supporting neurological repair and systemic healing. Longer fasts—especially those lasting 48–72 hours—have been shown to protect hematopoietic stem cells and promote immune system regeneration by reducing IGF-1 and PKA signaling, even reversing chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression (Hine & Mitchell, 2014).

Whole-Food Nutrition

While fasting gave my cells time to clean house, the fuel they used had to be clean. I focused on nutrient-dense whole foods—organic vegetables, fruits, eggs, and lean proteins. I eliminated processed foods and refined sugars entirely. It was simple: if it wasn’t real, I didn’t eat it. That included so-called “health” products like supplements and protein powders – because no matter how well-marketed, [they] are not real food. The energy mitochondria produce depends on the quality of the food we give them. No energy in, no healing out.

Chemical-Free Living

The more I learn, the less I consume. Well before my diagnosis, I had eliminated synthetic vitamins. At the time I was diagnosised I eliminated all sugar and anything I believed might interfere with healing. But over the past year, my awareness of endocrine-disrupting chemicals—in foods, packaging, personal care products, pharmaceuticals, over the counter drugs and household environments—has deepened. Today, I actively work to eliminate those chemicals from every part of my life. This late-stage realization has become essential to sustaining health and reducing cellular stress. I now view chemical-free living not as a preference, but as a foundation for long-term healing and resilience.

By minimizing toxins, I enhanced my body’s ability to pursue Cancer Recovery. This awareness was crucial in my journey towards optimal health.

Challenging the Protocol

The standard treatment for primary CNS lymphoma typically includes high-dose methotrexate and, in some cases, temozolomide (Temodar). But as I discovered through lived experience, many of the drugs prescribed for rare cancers—especially aggressive brain tumors—are experimental in nature, even if that fact isn’t always clearly communicated.

Temozolomide, for instance, is not FDA-approved for primary CNS lymphoma, yet it was included in my regimen. It is well-documented to deplete lymphocytes—the very immune cells my body needed to recover and defend itself. I had a violent reaction to it and stopped taking it almost immediately.

I also experienced severe or adverse responses to several other medications: rituximab, which triggered a dangerous reaction; leucovorin, which left me deeply depleted; and vancomycin, which led to an official allergy designation. At the time, I may have been told that some of these drugs were off-label or non-standard—but I can’t say I fully grasped the implications. In hindsight, I realize I had entered a protocol where trial-and-error was the norm.

And that’s the quiet truth few patients with rare diseases are told: we are often enrolled in real-time drug experimentation without the benefit of fully informed consent.

Eventually, I chose to step away. I stopped participating in the cycle. I chose to listen to my body, my scans, and my experience.

And the results have spoken for themselves.

This Isn’t Just Personal—It’s a Call to Reassess

This journey is not just personal; it represents a collective need for change in the approach to Cancer Recovery. We must explore all avenues available to us.

There is a need for brave questioning within modern oncology. I’m not claiming breath cures cancer. I’m not suggesting fasting alone eradicates tumors. But I am saying this: the body has capacities we ignore—and when supported properly, they can change outcomes in ways that don’t yet fit into standard charts.

Through my personal experience, I advocate for a broader understanding of Cancer Recovery. There’s a wealth of knowledge in our bodies that deserves exploration.

I’m stable. I’m thriving. And my last MRI shows no signs of tumor activity 17 months after stopping chemotherapy. If that doesn’t warrant investigation, what does?

This is not medical advice, nor a recommendation to abandon treatment. It is a lived account of one person’s experience—and an invitation to question what we think we know.

References:

- Huberman Lab Podcast: https://www.hubermanlab.com — multiple episodes explore breathwork physiology; I recommend browsing to find what speaks to you.

- Nestor, James. Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art. Riverhead Books, 2020.

- Hof, Wim. The Wim Hof Method. Sounds True, 2020.

- Buteyko Clinic: https://buteykoclinic.com

- Jamnadas, Pradeep. Galen Foundation. https://www.galenfoundation.org

YouTube Video Fasting for Survival

- Russell, R., et al. “Autophagy regulation by nutrient signaling.” Cell Research, 2014.

https://www.nature.com/articles/cr2013166

- Hine, C., & Mitchell, J. R. (2014). Saying no to drugs: Fasting protects hematopoietic stem cells from chemotherapy and aging. Cell Stem Cell, 14(6), 704–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.016

- US Food & Drug Administration. TEMODAR (temozolomide) Prescribing Information, Schering-Plough/Merck, 2016.

by Linda Wulf | Jun 10, 2025 | Chemical Exposure Unleashed, Main Blog |

Introduction: A Personal Awakening

I once believed that products approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were safe for use. But after my own battle with cancer, that illusion shattered. With the help of Grok AI and Chatbot GTP, I discovered that 7,157 unique chemicals—many of them untested or inadequately reviewed—persist in our food, drugs, packaging, and personal care products. This article is not just a critique of the FDA’s structure and oversight—it is a call for reform grounded in lived experience, regulatory history, and emerging science.

The FDA’s Flawed Governance: Overlapping Databases

The FDA’s governance is riddled with fragmentation, weak authority, and a troubling reliance on industry self-regulation. Responsibilities are split among the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), and a lightly managed oversight of cosmetics. The agency functions more like a passive archive for industry-submitted documents than an active safety watchdog.

The cornerstone of this problem is the ‘Generally Recognized as Safe’ (GRAS) process[1]. Originally intended to streamline approval of common food ingredients, GRAS allows substances to be deemed safe based on scientific evidence or expert consensus, often without FDA review. Today, companies can self-affirm safety by hiring their own experts, bypassing rigorous FDA oversight. Of the 3,970 substances in the FDA’s Substances Added to Food Database[2], roughly 3,670 have never undergone active FDA safety assessments.

Industry influence compounds the problem. From 1998 to 2025, the ultraprocessed food industry spent $1.4 billion lobbying, while pharmaceutical firms spent $6.3 billion. These efforts have blocked reform—most notably the closure of the GRAS self-affirmation loophole[3], which remains open despite HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s March 2025 directive to eliminate it[1].

Historical Context and Regulatory Evolution

When the FDA was created in 1906 under the Pure Food and Drugs Act, the food supply contained few synthetic chemicals. The agency’s early mission focused on preventing adulteration and mislabeling. With the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the FDA was empowered to conduct drug safety reviews. The 1958 Food Additives Amendment created the GRAS exemption[3], initially listing about 700 substances.

Over the decades, the GRAS process grew to include thousands of additional substances through self-affirmation. In 1997, a voluntary notification system further weakened FDA’s oversight. Parallel gaps in cosmetics, OTC drugs, and supplements evolved similarly. The result: 7,157 unique chemicals now permeate the U.S. consumer landscape, many without adequate federal oversight.

The Scale of Chemical Exposure

The FDA maintains several overlapping databases, each detailing different chemical categories:

- Substances Added to Food (3,970 substances): Includes sodium benzoate, which can form carcinogenic benzene when combined with ascorbic acid[4], and monocalcium phosphate, a leavening agent linked to health risks from high phosphorus intake[5].

- Inventory of Food Contact Substances (3,652 substances)[7].

- Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS): 451 entries (370 substances), including carrageenan, linked to inflammation and cancer risks[8].

- Inactive Ingredients Database (9,196 entries, 1,048 unique substances): Includes propylparaben, an endocrine disruptor[9].

- Dietary Supplement Label Database (205,782 labels): Includes ascorbic acid, which poses risks of overexposure in self-affirmed uses[10].

These databases often rely on industry data, not independent review, leaving Americans exposed to substances never meaningfully tested for long-term safety.

The Hidden Health Risks

Of the 7,157 unique chemicals in circulation, many are endocrine disruptors—compounds that interfere with hormonal systems[11]. These are linked to obesity, infertility, diabetes, and even cancer. Research suggests up to 20% of food additives may have endocrine-disrupting properties[12].

Notable examples:

- Propylparaben in drugs and lotions mimics estrogen and may impair reproductive health[13].

- Carrageenan used in food and toothpaste contributes to colitis and chronic inflammation[14].

- Sodium benzoate, still legal, may generate carcinogenic byproducts when paired with vitamin C[6].

Consumers often assume FDA approval means safety, but unless they dig into obscure databases or advocacy sites, they’re unaware of these systemic risks.

Overlapping Oversight and Personal Care Risks

Personal care products pose unique risks. Ingredients like propylparaben, commonly found in creams and lotions, are absorbed through the skin. Despite their systemic impact, cosmetics remain under-regulated. No dedicated FDA database exists to track their safety, perpetuating exposure through regulatory neglect.

Seeking Transparency

For proactive consumers, tools exist but require effort. The Inactive Ingredients Database (IID)[9] and apps like Yuka[15] allow users to check ingredient profiles, but they lack plain-language risk summaries. Meaningful transparency will require integrating FDA databases into a single, user-friendly platform.

A Call for Comprehensive Reform

To protect public health, the FDA must:

- Consolidate CFSAN, CDER, and cosmetic oversight into one cohesive regulatory body.

- Eliminate GRAS self-affirmation and require FDA review of all safety claims.

- Limit industry lobbying and funding of research tied to regulatory decisions.

- Create a single, public database of all approved chemicals with searchable summaries.

- Despite evidence of harm, unsafe substances often remain in use for years due to slow regulatory action, perpetuating public health risks.

- Immediately restrict high-risk substances like Red No. 40[16], and propylparaben instead of phasing them out over the years.

Until reform arrives, Americans must become their own watchdogs—researching the safety of food, medication, personal care products, and even their tap water.

by Linda Wulf | Mar 24, 2025 | Main Blog |

Imagine picking up a snack from the grocery shelf—crackers, soda, or a candy bar. You scan the ingredients, spotting familiar names like sugar or salt, and maybe some tongue-twisters like “sodium benzoate” or “xanthan gum.” What you don’t see is a quiet stamp of approval baked into U.S. law: “Generally Recognized as Safe,” or GRAS. It’s a term most of us have never heard of, yet it governs thousands of substances in our food. Enshrined in regulation since 1958, GRAS was meant to keep us safe. But over decades, it’s morphed into a system so entrenched that we’re consuming additives daily—some of which might be silently harming us, and we don’t even know it.

What Is GRAS?

GRAS stands for “Generally Recognized as Safe,” a designation created by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to classify food ingredients that don’t need rigorous premarket testing. If a substance is widely accepted by qualified experts as safe—based on scientific data or a long history of use—it gets the GRAS label and can go straight into your food. Think of it as a fast-pass lane: sugar, vinegar, and spices sailed through because they’ve been used forever, while new chemicals can qualify with enough expert agreement.

The idea sounds reasonable—why bog down the FDA with red tape for stuff everyone trusts? But here’s the catch: GRAS isn’t just a handful of pantry staples. It’s thousands of additives—flavorings, preservatives, thickeners—slipped into processed foods, from your morning cereal to your evening takeout. And as the system evolved, the question shifted from “Is this safe?” to “Who’s even checking?”

How It Started: The 1958 Food Additives Amendment

Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) was born in a simpler time. Before the 1950s, the FDA had broad authority to police food safety, but the rise of synthetic chemicals—think artificial flavors and stabilizers—overwhelmed the system. In 1958, Congress passed the Food Additives Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, demanding premarket approval for new additives unless they were GRAS. The law defined GRAS as substances “generally recognized, among experts qualified by scientific training and experience,” as safe based on science or common use before 1958.

Back then, the FDA took the lead. Companies petitioned the agency to affirm ingredients like caffeine or citric acid as GRAS, and the FDA published its rulings in the Code of Federal Regulations. It was a manageable list, with the agency carefully vetting each substance. The goal? Protect consumers while letting innovation flow. For a while, it worked.

How It Evolved: From Oversight to Loophole

Fast-forward to the 1990s, and the cracks started showing. The FDA, swamped with petitions and short on resources, proposed a game-changer in 1997: ditch the formal affirmation process for a voluntary “notification” system. Companies could now self-affirm a substance as GRAS, send the FDA their safety data (or not), and start using it unless the agency objected. By 2016, this became official policy. The shift was seismic—oversight moved from the FDA’s desk to industry boardrooms.

The numbers tell the story. In the petition era, it’s estimated that fewer than 400 substances earned FDA-affirmed GRAS status, though exact figures are hard to confirm without historical records. Today, a database of GRAS substances downloaded in July 2024 lists exactly 3,972 entries—covering everything from vanilla extract to obscure flavorings like “(+/-)-2-Methyltetrahydrofuran-3-thiol Acetate.” These additives touch nearly every processed bite you take.

Enshrined in Law, Embedded in Our Lives

That 1958 amendment enshrined GRAS as a legal fixture, and its evolution has made it untouchable. Companies love it—no lengthy approvals, no mandatory FDA sign-off. The FDA leans on it too, stretched thin by budget cuts and a flood of new ingredients. But what about us, the eaters? We’re left trusting a system where safety is assumed until proven otherwise—sometimes decades too late.

Take partially hydrogenated oils, commonly known as trans fats: GRAS for years, they clogged arteries until science linked them to heart disease in the 1990s. The FDA didn’t ban them until 2015, with a full phase-out by 2021—20 years of delay while we ate. Or consider caffeine-spiked alcoholic drinks like Four Loko, yanked in 2010 after ER visits spiked, yet similar combos still linger in loopholes. These aren’t outliers; they’re symptoms of a system that waits for harm to scream before it whispers “stop.”

The Unseen Cost

Here’s the kicker: we don’t know what’s killing us because GRAS hides in plain sight. Some additives—like ethylene oxide, a known carcinogen, or alkanet root extract linked to liver toxicity—were once deemed GRAS by the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association (FEMA) but have since been stripped of that status due to safety concerns. Yet they may still linger in our food if companies self-affirm their safety because the FDA’s hands are tied. Worse, no one tracks how many of these 3,972 additives a body can absorb or what happens when they combine—like drugs, they have effects that linger, burdening the body’s cleanup systems, yet they’re tested in isolation, not as the chemical cocktail we consume.

This self-affirmation loophole even extends to the vitamin and supplement market, where untested compounds can slip into products we assume are safe. And that’s just food—add in exposures from over-the-counter drugs, pharmaceuticals, and beauty products (which the FDA barely regulates, leaving safety to companies), and the disconnect grows: your body doesn’t care about regulatory silos; it processes the total exposure.

Meanwhile, new science—like the Human Microbiome Project’s discoveries since 2007 showing how additives can disrupt gut bacteria linked to health—reveals risks the sluggish GRAS system can’t keep up with: how can regulation protect us when it lags decades behind what we’re learning about our bodies? Industry self-policing means no one’s compelled to pull the plug until the evidence is overwhelming, and even then, it’s a slog. We’re consuming a chemical cocktail daily, legally enshrined, and most of us don’t even know what GRAS stands for.

Conclusion

This is just the beginning. GRAS started as a safeguard, evolved into a loophole, and now sits as a silent giant in our food system. Next time you grab a snack, ask yourself: who decided this was safe—and how long will it take to find out if they were wrong? More importantly, what is your body telling you?

Explore our curated resources for in-depth insights, expert guidance, and valuable tools to expand your knowledge and stay informed.

by Linda Wulf, with assistance from Grok (xAI)