Imagine picking up a snack from the grocery shelf—crackers, soda, or a candy bar. You scan the ingredients, spotting familiar names like sugar or salt, and maybe some tongue-twisters like “sodium benzoate” or “xanthan gum.” What you don’t see is a quiet stamp of approval baked into U.S. law: “Generally Recognized as Safe,” or GRAS. It’s a term most of us have never heard of, yet it governs thousands of substances in our food. Enshrined in regulation since 1958, GRAS was meant to keep us safe. But over decades, it’s morphed into a system so entrenched that we’re consuming additives daily—some of which might be silently harming us, and we don’t even know it.

What Is GRAS?

GRAS stands for “Generally Recognized as Safe,” a designation created by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to classify food ingredients that don’t need rigorous premarket testing. If a substance is widely accepted by qualified experts as safe—based on scientific data or a long history of use—it gets the GRAS label and can go straight into your food. Think of it as a fast-pass lane: sugar, vinegar, and spices sailed through because they’ve been used forever, while new chemicals can qualify with enough expert agreement.

The idea sounds reasonable—why bog down the FDA with red tape for stuff everyone trusts? But here’s the catch: GRAS isn’t just a handful of pantry staples. It’s thousands of additives—flavorings, preservatives, thickeners—slipped into processed foods, from your morning cereal to your evening takeout. And as the system evolved, the question shifted from “Is this safe?” to “Who’s even checking?”

How It Started: The 1958 Food Additives Amendment

Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) was born in a simpler time. Before the 1950s, the FDA had broad authority to police food safety, but the rise of synthetic chemicals—think artificial flavors and stabilizers—overwhelmed the system. In 1958, Congress passed the Food Additives Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, demanding premarket approval for new additives unless they were GRAS. The law defined GRAS as substances “generally recognized, among experts qualified by scientific training and experience,” as safe based on science or common use before 1958.

Back then, the FDA took the lead. Companies petitioned the agency to affirm ingredients like caffeine or citric acid as GRAS, and the FDA published its rulings in the Code of Federal Regulations. It was a manageable list, with the agency carefully vetting each substance. The goal? Protect consumers while letting innovation flow. For a while, it worked.

How It Evolved: From Oversight to Loophole

Fast-forward to the 1990s, and the cracks started showing. The FDA, swamped with petitions and short on resources, proposed a game-changer in 1997: ditch the formal affirmation process for a voluntary “notification” system. Companies could now self-affirm a substance as GRAS, send the FDA their safety data (or not), and start using it unless the agency objected. By 2016, this became official policy. The shift was seismic—oversight moved from the FDA’s desk to industry boardrooms.

The numbers tell the story. In the petition era, it’s estimated that fewer than 400 substances earned FDA-affirmed GRAS status, though exact figures are hard to confirm without historical records. Today, a database of GRAS substances downloaded in July 2024 lists exactly 3,972 entries—covering everything from vanilla extract to obscure flavorings like “(+/-)-2-Methyltetrahydrofuran-3-thiol Acetate.” These additives touch nearly every processed bite you take.

Enshrined in Law, Embedded in Our Lives

That 1958 amendment enshrined GRAS as a legal fixture, and its evolution has made it untouchable. Companies love it—no lengthy approvals, no mandatory FDA sign-off. The FDA leans on it too, stretched thin by budget cuts and a flood of new ingredients. But what about us, the eaters? We’re left trusting a system where safety is assumed until proven otherwise—sometimes decades too late.

Take partially hydrogenated oils, commonly known as trans fats: GRAS for years, they clogged arteries until science linked them to heart disease in the 1990s. The FDA didn’t ban them until 2015, with a full phase-out by 2021—20 years of delay while we ate. Or consider caffeine-spiked alcoholic drinks like Four Loko, yanked in 2010 after ER visits spiked, yet similar combos still linger in loopholes. These aren’t outliers; they’re symptoms of a system that waits for harm to scream before it whispers “stop.”

The Unseen Cost

Here’s the kicker: we don’t know what’s killing us because GRAS hides in plain sight. Some additives—like ethylene oxide, a known carcinogen, or alkanet root extract linked to liver toxicity—were once deemed GRAS by the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association (FEMA) but have since been stripped of that status due to safety concerns. Yet they may still linger in our food if companies self-affirm their safety because the FDA’s hands are tied. Worse, no one tracks how many of these 3,972 additives a body can absorb or what happens when they combine—like drugs, they have effects that linger, burdening the body’s cleanup systems, yet they’re tested in isolation, not as the chemical cocktail we consume.

This self-affirmation loophole even extends to the vitamin and supplement market, where untested compounds can slip into products we assume are safe. And that’s just food—add in exposures from over-the-counter drugs, pharmaceuticals, and beauty products (which the FDA barely regulates, leaving safety to companies), and the disconnect grows: your body doesn’t care about regulatory silos; it processes the total exposure.

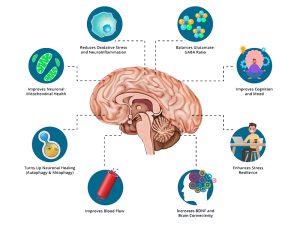

Meanwhile, new science—like the Human Microbiome Project’s discoveries since 2007 showing how additives can disrupt gut bacteria linked to health—reveals risks the sluggish GRAS system can’t keep up with: how can regulation protect us when it lags decades behind what we’re learning about our bodies? Industry self-policing means no one’s compelled to pull the plug until the evidence is overwhelming, and even then, it’s a slog. We’re consuming a chemical cocktail daily, legally enshrined, and most of us don’t even know what GRAS stands for.

Conclusion

This is just the beginning. GRAS started as a safeguard, evolved into a loophole, and now sits as a silent giant in our food system. Next time you grab a snack, ask yourself: who decided this was safe—and how long will it take to find out if they were wrong? More importantly, what is your body telling you?

Explore our curated resources for in-depth insights, expert guidance, and valuable tools to expand your knowledge and stay informed.

by Linda Wulf, with assistance from Grok (xAI)

Linda Wulf

Linda Wulf is a cancer rebel, advocate, and independent researcher. Diagnosed in 2023 with primary CNS lymphoma, she declined standard chemotherapy and pursued a root-cause, immune-supporting path. Twenty-three months cancer-free via root-cause approach.