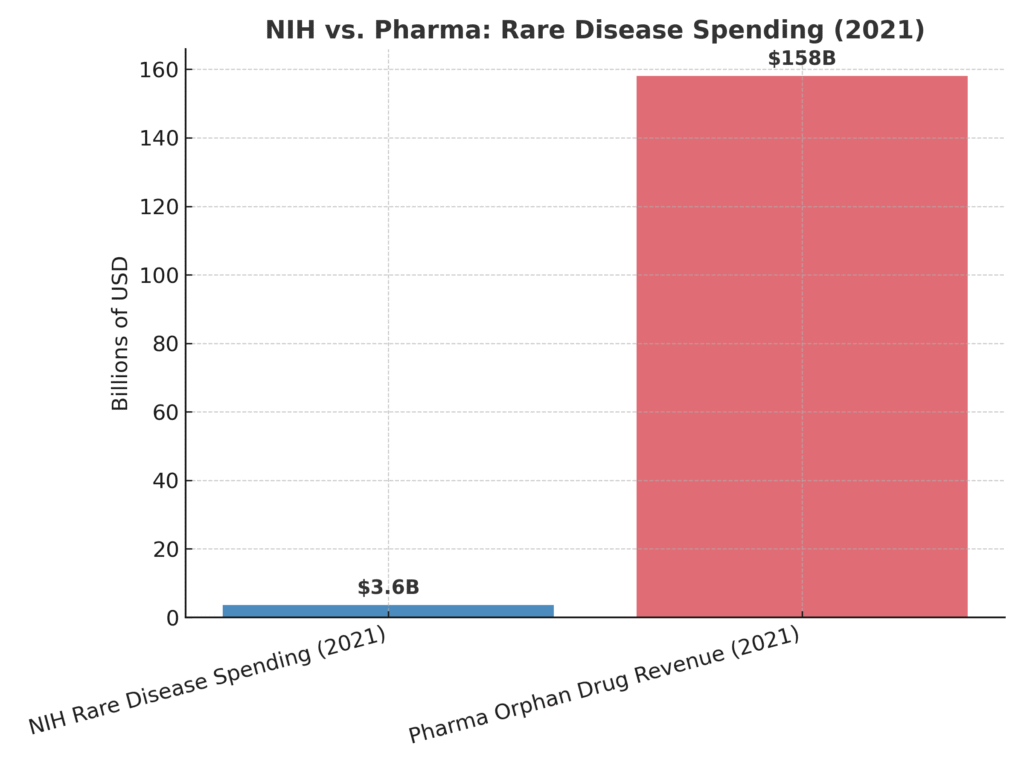

Billions flow into drug pipelines while root causes like infection, inflammation, and chemicals are ignored.

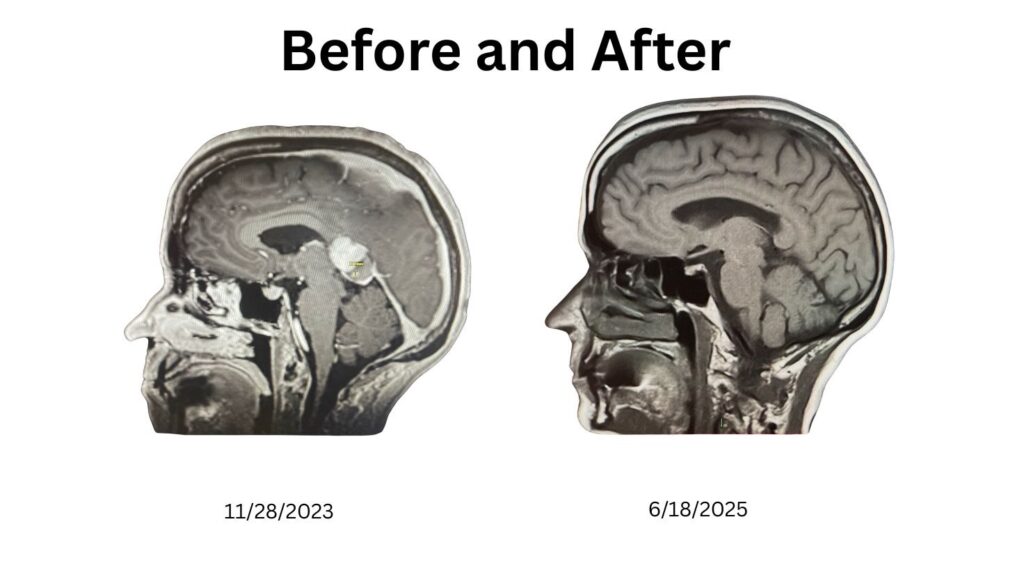

They told me I had an ‘incurable, inoperable brain cancer.’ But the word incurable wasn’t true — it was a reflection of how our system defines cure. In medicine today, cures almost always mean drugs. And when the cause doesn’t fit that drug-first narrative, it gets ignored.

My cancer didn’t come from bad luck or a random mutation. It followed years of chronic dental infections — a connection my doctors dismissed with the words: *’We don’t do teeth.’* That single line summed up the blind spot baked into our healthcare system: it doesn’t look for causes, it looks for prescriptions.

The Incentives That Shape Medicine

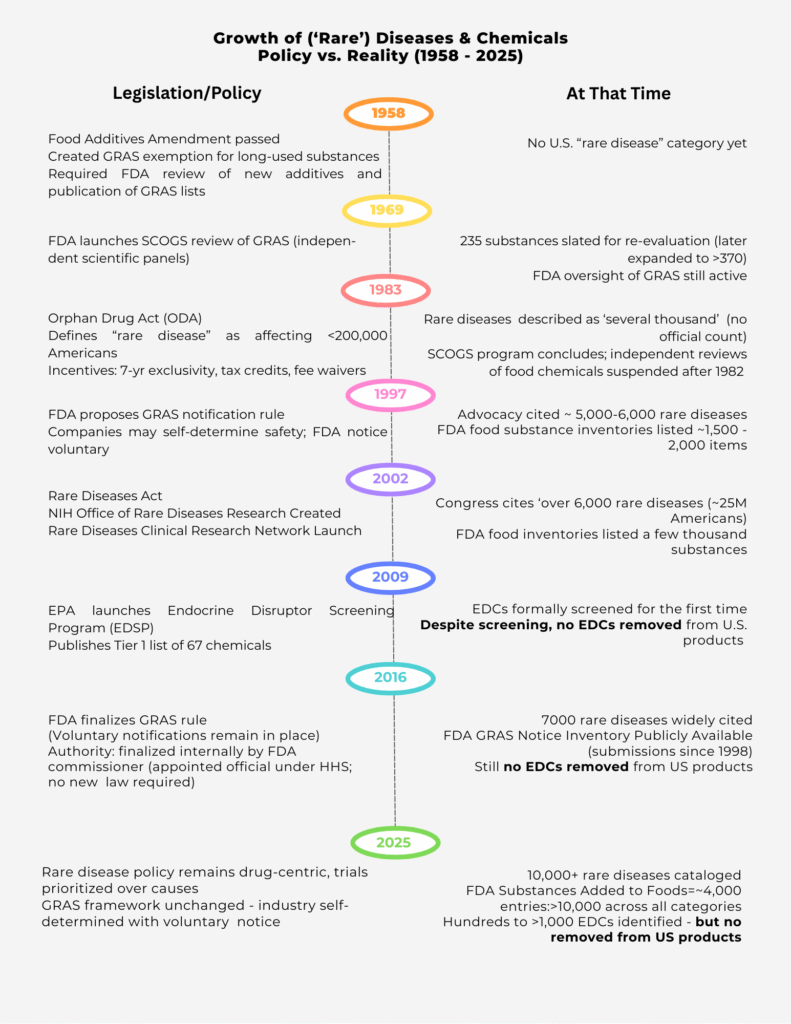

Since the Orphan Drug Act of 1983, a ‘rare disease’ has been defined as one that affects fewer than 200,000 Americans. The law created powerful incentives for companies: seven years of market exclusivity, tax credits for clinical trials, and waived FDA fees. In 2002, the Rare Diseases Act expanded NIH funding, creating the Office of Rare Diseases Research. Both laws were designed to stimulate innovation — and they did. But the innovation was channeled almost exclusively toward drugs, not prevention, not causes. Billions have flowed into the pipeline.

The government doesn’t just regulate this system — it participates, benefiting from patents, royalties, and partnerships. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry reaps trillions in revenues. The balance is obvious: cures are defined as drugs, not as eliminating the conditions that cause disease in the first place.

A Timeline of Oversight—and Abandonment

The government once had a more balanced approach. In 1958, the Food Additives Amendment created the ‘generally recognized as safe’ (GRAS) category. By 1969, FDA launched the SCOGS program, where independent scientific panels reviewed hundreds of food chemicals. Those reviews concluded in 1982, and no significant removals followed. After that, independent oversight was suspended. In 1983, the Orphan Drug Act shifted the focus squarely toward drugs.

In 1997, FDA proposed a new rule allowing companies to self-certify chemical safety with voluntary notification to the agency. By 2016, the GRAS rule was finalized — not by Congress, but internally by the FDA Commissioner, an appointed official. That single decision cemented a framework where industry now polices itself.

Meanwhile, in 2009, the EPA launched the Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program (EDSP), its first formal attempt to evaluate endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). But here too, the promise fell flat. As the Inspector General confirmed in 2021, after more than a decade of screening, **not a single EDC has been removed from U.S. products.**

What Gets Ignored

When the system tilts this far toward pharmaceuticals, what gets left behind are the real root causes of disease. Chronic infections. Inflammation. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Environmental exposures. Metabolic dysfunction tied to our diets. Each of these can drive disease, yet none of them come with tax credits, exclusivity periods, or billion-dollar incentives. Instead, we pour billions into trials for the next drug, while causes remain unaddressed.

The Bigger Picture

The policies guiding rare diseases were designed with good intentions, but the outcome has been predictable. Billions have been spent on research and drug development, while independent reviews of food chemicals were halted decades ago and endocrine disruptor screening has produced no removals. Patients like me are told our diseases are genetic, mysterious, or ‘bad luck,’ even when the cause may be as basic as a chronic infection. I was told my disease was ‘incurable,’ yet I have no disease. Until root causes are addressed, patients will remain trapped in a drug-first system — a system that is not broken, but working exactly as designed.

Linda Wulf

Linda Wulf is a cancer rebel, advocate, and independent researcher. Diagnosed in 2023 with primary CNS lymphoma, she declined standard chemotherapy and pursued a root-cause, immune-supporting path. Twenty-three months cancer-free via root-cause approach.