Realizing the Chemical Load

About this time last year—July 2024—I started doing one of those strange and sobering things people do when they begin consciously preparing for the end: clearing out clutter, sorting through forgotten corners of the house, and asking what matters. That beautiful July day, I found myself sorting through my stuff, trying to make things easier for whoever might someday have to deal with it—asking: What to keep? What to toss? Why do I even have this?

While scanning my shelves for books I could let go of, I paused at a volume that had followed me through several moves. I had boxed it up and shipped it west over a decade earlier from my mother’s house, when I was helping her relocate for what would be her final days. She passed in 2014, but the book had remained unread on my shelves ever since—until now, when I was beginning to contemplate my own demise.

The book was titled Du Pont: The Autobiography of an American Enterprise, published in 1952 to commemorate the company’s 150th anniversary. Inside was a mimeographed letter addressed to my mom, who had worked in Du Pont’s advertising department that year.

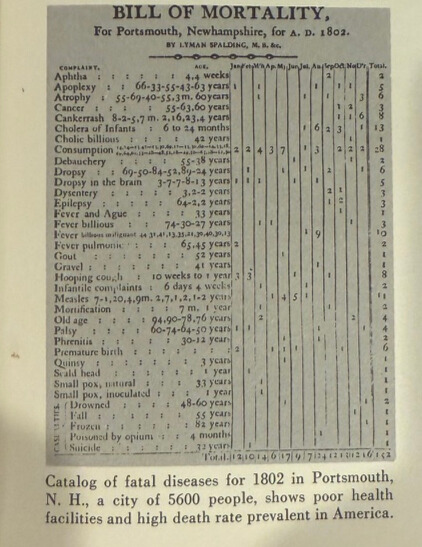

What ultimately caught my attention wasn’t the corporate history but a curious image printed on page 5: the “Bill of Mortality for Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for A.D. 1802.” A stark ledger of the 152 people who died that year in a small New England city. The typed and handwritten entries listed causes of death from “Aphtha” to “Suicide,” and I found myself drawn in—not just by the details, but by the contrast to now. What were we dying from then, compared to today?

Figure 1: Bill of Mortality, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1802, printed in DuPont: The Autobiography of an American Enterprise (1952), showing 152 deaths, mostly from infectious diseases like cholera, measles, and whooping cough. Only three cancer cases were noted, with minimal neurological mentions.

As I studied the faded image, the differences were profound. In 1802, only three deaths were attributed to cancer and none to heart disease—conditions that today account for nearly half of all U.S. deaths. Neurological illnesses were also uncommon, with just twelve cases listed under older terms like “apoplexy,” “epilepsy,” and “palsy.” Instead, the ledger was filled with infectious threats: measles, cholera, whooping cough, and dysentery.

Of the 152 total deaths recorded in Portsmouth that year, 50 were children under the age of 15, including six premature births. In a world with no antibiotics, no vaccines, and poor sanitation, the greatest threat to life was microbial—not metabolic. Chronic illness was rare, and survival into old age, while possible, was far from guaranteed.

By the 1930s, the landscape of death had shifted dramatically. Infectious diseases that once dominated life had been largely tamed by antibiotics, vaccines, clean water systems, and public health reforms. In 1906, the Pure Food and Drugs Act was passed, and enforcement was assigned to the Bureau of Chemistry—the early predecessor to today’s FDA. It wasn’t until 1930 that the modern Food and Drug Administration was officially named. These were triumphs. Life expectancy rose. The killers of 1802 were, it seemed, under control.

But as I lingered over that 1802 ledger, a different question came into focus: If we’d conquered those ancient plagues, why are we now dying from cancer, heart disease, and neurological disorders at rates unimaginable two centuries ago?

That’s When It Hit Me

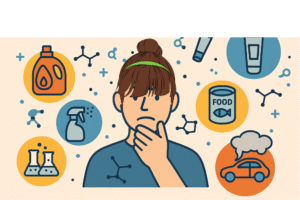

We had traded one threat for another. Microbes for molecules. Today, the average American body is exposed to thousands of synthetic chemicals—every single day. And not in trace amounts. These are in our food, our packaging, our personal care products, our medicine cabinets—even the supplements we take to “stay healthy.” Unlike the short, violent threat of infection, this chemical load accumulates—quietly, invisibly—until something breaks.

As I began researching what became my article, The Toxic Web, I discovered the scale of the problem: 7,157 unique chemicals are actively used across FDA databases for food, drugs, packaging, and personal care products. Many have never undergone a meaningful safety review. Others were grandfathered in decades ago under loopholes like GRAS—”Generally Recognized as Safe”—which allow companies to self-certify ingredients without oversight.

And so my “aha” moment wasn’t just academic—it was personal. I realized: this is what we’re up against now.

So I made a change. A real one. I stopped waiting for someone to protect me. I eliminated every unnecessary chemical I could find—starting with my plate and my shower. No additives. No preservatives. No medications, over the counter or otherwise unless there was a clear, tested need. No more synthetic lotions, no more “natural” products with mystery ingredients. I cleaned up what went in and what went on.

This wasn’t a rejection of science. It was a return to balance. A conscious choice to stop feeding the silent storm brewing inside me.

Once I understood the scale of the chemical load we’re all living under, I began to do something both radical and simple: I started paying attention.

Not in a paranoid way. In a quiet, curious way. I began watching my body—closely—for how it responded to chemicals. I had downloaded the Yuka app months before, but now I was more aggressive, scanning every label I could find. What was in my lotion? My shampoo? My toothpaste? My almond butter? Every product had a backstory—often a toxic one. Most people around me assumed that if it was on a shelf, it must be safe. But I had stopped believing that. And what I started noticing confirmed my doubts.

Let Me Share with You One Moment in Particular

It was my granddaughter Bexly’s birthday, August 3, 2024. I went to her party trying to strike the balance I’d been practicing—avoiding additives without being a pain. I don’t want to be the crazy “Lola” who won’t eat anything. So that evening, I skipped the bottled salad dressing (most contain endocrine disruptors), had a little bit of salad greens knowing it might carry some pesticide residue, and then joined in the celebration: Papa Murphy’s pizza and a slice of commercially prepared birthday cake—frosted in its cotton-candy-colored glory.

I felt fine that night. It was so good—I hadn’t indulged in a sweet cake treat in months. But the next morning at 7 a.m., I stood up and was completely surprised by what happened. I jumped up and immediately realized my balance was completely off. The room was shaky. I wasn’t dizzy in the usual sense—I was disoriented. My equilibrium had collapsed. It took until nearly 1 p.m. before I started feeling normal again, like I could walk without tripping or falling.

In hindsight, I realized I had experienced a delayed neurotoxic response. The vivid dyes in that cake frosting—like Red 40 and Blue 1—are flagged by Yuka and others as neurotoxic and endocrine-disrupting. My nervous system had taken the hit. That incident wasn’t a fluke—it was my body’s response to the tiny bit of neurotoxins in that cake.

It occurred to me at that moment that maybe doctors shouldn’t just ask us “old folks” if we’re feeling off balance—they should be asking what kind of birthday cake we ate last night.

From that point on, I became meticulous and diligent about noticing. I cut out unnecessary chemicals wherever I could—ditching synthetic lotions, shampoos, and soaps. I had stopped taking supplements years earlier, after watching a close friend rapidly decline from glioblastoma. I couldn’t help but wonder whether the concentrated compounds she’d taken in an effort to “stay healthy” had, ironically, hastened her decline. It was only a hunch—but strong enough to change my behavior at the time.

I buy organic whenever possible. I practiced delayed eating—12 to 14 hours regularly. And I paid close attention to my own reactions—especially to subtle shifts: dry eyes, brain fog, mood changes, and fatigue. These became signals. Data points. Feedback.

This wasn’t about fear. It was about awareness—the act of noticing of listening to a body that had been shouting all along but had gone unheard.

And still, I live. I go out. I laugh with friends. I eat in restaurants—carefully. I don’t let vigilance turn into obsession. But now, I live by one rule: if I can avoid it, I will.

Because once you start noticing, you can’t unsee it. And once your body shows you the cost, you stop pretending the price is acceptable.

So that’s where I’ll leave this—for now. Just notice. Start there. Your body might be saying more than you think. Mine was.

Linda Wulf

Linda Wulf is a cancer rebel, advocate, and independent researcher. Diagnosed in 2023 with primary CNS lymphoma, she declined standard chemotherapy and pursued a root-cause, immune-supporting path. Twenty-three months cancer-free via root-cause approach.